my dear friends

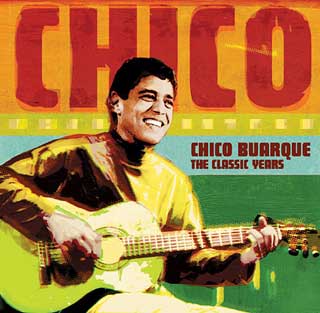

My brother Leslie once came back from Brazil with a gift for me. A cassette tape. Remember these relics of another age? Remember that flimsy brown strip of magnetic tape that would melt in the summer, snap in the winter and unravel when in a bad mood? To save our music, we learned the now obsolete skill of repairing broken tapes. We became experts in the art of splicing, of rolling pencils in the tape wheel, of using paper clips to smooth the wrinkles caused by the snags…Let no one tell you otherwise: no surgeon coming out of medical school had a more precise and delicate touch than a music lover repairing a cassette tape. Of course, none of this is of any importance today as no one listens to cassettes anymore, and no one needs them repaired. All these precious moments spent… I should have learned Japanese instead. Of course, ever the romantic, when I took a language course in college, I chose Russian because I wanted to read Maiakovski’s poems in the original. (After a couple of semesters and an inseparable dictionary -memento kept as sign of my folly- I managed to decipher PRAVDA’s subtitles and to write my name before I gave up that pursuit.) But forgive my rambling. The brazilian cassette? It was by Chico Buarque, a singer I had never heard of before. Although I have visited Brazil several times, Eu Não Falo Português.. Oh, as a fluent Spanish speaker, I get along fine in an idiom I invented, a bizarre mélange of both (but isn’t language a living entity ever evolving, ever changing? No?) So, although I didn’t speak Portuguese, I loved the music and I loved his voice. Chico Buarque sang about people struggling, street kids, prostitutes, about love in times of trouble, about censorship. .. which brings me back to that cassette tape, as one of my favorite Buarque songs is Meu caro amigo (My dear friend).

My dear friend, please forgive me, if I can’t pay you a visit, but since I found someone to carry a message, I’m sending you news on this tape. Here we play soccer, there’s lots of samba, lots of choro and rock’n’roll. Some days it rains, some days it’s sunny but I want to tell you that things here are pretty dark. Here, we’re wheeling and dealing for survival, and we’re only surviving because we’re stubborn. And everyone’s drinking because without cachaça, nobody survives this squeeze.

My dear friend, please forgive me, if I can’t pay you a visit, but since I found someone to carry a message, I’m sending you news on this tape. Here we play soccer, there’s lots of samba, lots of choro and rock’n’roll. Some days it rains, some days it’s sunny but I want to tell you that things here are pretty dark. Here, we’re wheeling and dealing for survival, and we’re only surviving because we’re stubborn. And everyone’s drinking because without cachaça, nobody survives this squeeze.

My dear friend, I don’t want to bother you or make you homesick, but I can’t avoid telling you the news. Here, we’re hustling and dealing for our daily bread with spite and a bad taste in our mouths. And everybody’s smoking, because without a smoke, nobody survives this squeeze.

My dear friend, I wanted to call you, but the price of a call is nothing to laugh about. I’m distressed because I want you to know what’s going on. Here, there’s pushing and shoving and we have to swallow so many lies. And everybody’s loving, because without a little loving, nobody survives this squeeze.

My dear friend, I really wanted to write to you but the mail is a risky thing. But if this goes past them (the government), I’ll try to send fresh news on this tape… Marieta (Buarque’s wife) sends a kiss for you, a kiss for the family, for Cecilia, for the kids; Francisco (Buarque himself) also sends his regards. All the best and Goodbye…

So, there I was looking through some boxes this evening and I found all these cassettes, and among them was my Chico Buarque tape. I no longer have a cassette player and I can’t verify this but the last time I played this, it was hissing and would sometimes get stuck right in the last part of the song. It brought back so many memories and I thought I’d give you the gift my brother gave me 20 years ago. So for you, my dear friends, meus caros amigos, here’s

So, there I was looking through some boxes this evening and I found all these cassettes, and among them was my Chico Buarque tape. I no longer have a cassette player and I can’t verify this but the last time I played this, it was hissing and would sometimes get stuck right in the last part of the song. It brought back so many memories and I thought I’d give you the gift my brother gave me 20 years ago. So for you, my dear friends, meus caros amigos, here’s May you enjoy him as much as I did:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WPEPj3wpSb0

Other favorite Buarque songs:

Construção

Apesar de você

Calice

Funeral de um lavrador

Francisco Buarque de Hollanda

Francisco Buarque de Hollanda(born June 19, 1944 in Rio de Janeiro) is a Brazilian poet, singer, musician, songwriter and novelist who become famous for his music which comments on Brazil’s social, economic and cultural situation. His latest book, Budapeste, achieved great critical acclaim and won the Prêmio Jabuti, a brazilian award similar to The Booker Prize Award.

“I’m an amateur,” says the singer-songwriter turned bestselling novelist who turned 64 this June, “I’m not a professional. Yet somehow I manage to get away with it.” Modesty is a well-known Buarque trait. He is notoriously press-shy. To observe and write without exposing himself is what he has always sought for himself. Yet he is a man who has helped define Brazilian culture for the past four decades. In Brazil, he is nothing short of a national treasure. His lyrics are studied as part of the Portuguese BA curriculum and his songs are hummed and sung across the country.

‘Music kind of kidnapped me’ he says. Starting out composing songs in the Sixties, he went on to write hundreds of them. His gift as a social commentator was to inhabit the lives of Brazil’s disenfranchised. ‘Construcao’, a surrealist fantasy about a construction worker falling to his death became a popular classic, enamouring him to a public struggling with political repression under military rule. Exile is a recurrent theme in Buarque’s life and work. Buarque himself was jailed briefly and went into exile in Italy and France. He learnt the importance of words at a time when words were banned. Forced to submit his songs to government censors, nearly two-thirds of his material was rejected. “It was a challenge,” he says. ” I had to write 20 songs in order to get 2 past the censors.”

‘Music kind of kidnapped me’ he says. Starting out composing songs in the Sixties, he went on to write hundreds of them. His gift as a social commentator was to inhabit the lives of Brazil’s disenfranchised. ‘Construcao’, a surrealist fantasy about a construction worker falling to his death became a popular classic, enamouring him to a public struggling with political repression under military rule. Exile is a recurrent theme in Buarque’s life and work. Buarque himself was jailed briefly and went into exile in Italy and France. He learnt the importance of words at a time when words were banned. Forced to submit his songs to government censors, nearly two-thirds of his material was rejected. “It was a challenge,” he says. ” I had to write 20 songs in order to get 2 past the censors.” Playing ‘futebol’ with Bob Marley. Soccer is his earliest and most enduring passion. “I started playing soccer when I was four years old, and I still play every week.”

Playing ‘futebol’ with Bob Marley. Soccer is his earliest and most enduring passion. “I started playing soccer when I was four years old, and I still play every week.” Meu caro amigo:

Meu caro amigo:L’une des chansons les plus connues de Chico Buarque. Une lettre en forme de chanson adressée à Augusto Boal, exilé à ce moment-là.

Mon cher ami tu m’excuses s’il te plait

Se eu não lhe faço uma visita

Si je ne te rends pas visite

Mas como agora apareceu um portador

Mais comme maintenant vient d’apparaître un messager

Mando notícias nessa fita

Je t’envoie des nouvelles sur cette cassette

Aqui na terra ’tão jogando futebol

Ici au pays on joue au football

Tem muito samba, muito choro e rock’n’ roll

Il y a beaucoup de samba beaucoup de choro et de rock’n’roll

Uns dias chove, noutros dias bate sol

Des jours il pleut, d’autres le soleil cogne

Mas o que eu quero é lhe dizer que a coisa aqui ’tá preta

Mais ce que je veux dire c’est que les choses ici vont mal

Muita mutreta pra levar a situação

Beaucoup de combines pour supporter la situation

Que a gente vai levando de teimoso e de pirraça

Qu’on supporte avec obstination et malice

E a gente vai tomando, que também, sem a cachaça

Et qu’on boit beaucoup, aussi, parce que sans la cachaça

Ninguém segura esse rojão

Personne ne supporte cette galère

Meu caro amigo eu não pretendo provocar

Mon cher ami je ne prétend pas provoquer

Nem atiçar suas saudades

Ni ranimer ta nostalgie

Mas acontece que não posso me furtar

Mais il se trouve que je ne peux me soustraire

A lhe contar as novidades

A te raconter les nouveautés

Aqui na terra ’tão jogando futebol

Ici au pays on joue au football

Tem muito samba, muito choro e rock’n’ roll

Il y a beaucoup de samba beaucoup de choro et de rock’n’roll

Uns dias chove, noutros dias bate sol

Des jours il pleut, d’autres le soleil cogne

Mas o que eu quero é lhe dizer que a coisa aqui ’tá preta

Mais ce que je veux dire c’est que les choses ici vont mal

É pirueta pra cavar o ganha-pão

Faire des pirouettes pour arracher son gagne-pain

Que a gente vai cavando só de birra, só de sarro

Qu’on arrache de têtu, de capricieux

E a gente vai fumando que, também, sem um cigarro

Et qu’on fume, aussi, parce que sans la cigarette

Ninguém segura esse rojão

Personne ne supporte cette galère

Meu caro amigo eu quis até telefonar

Mon cher ami j’ai même voulu téléphoner

Mas a tarifa não tem graça

Mais le coût n’a rien d’amusant

Eu ando aflito pra fazer você ficar

J’ai une envie folle de te mettre

A par de tudo que se passa

Au courant de ce qui se passe

Aqui na terra ’tão jogando futebol

Ici au pays on joue au football

Tem muito samba, muito choro e rock’n’ roll

Il y a beaucoup de samba, beaucoup de choro et rock’n’roll

Uns dias chove, noutros dias bate sol

Des jours il pleut, d’autres le soleil cogne

Mas o que eu quero é lhe dizer que a coisa aqui ’tá preta

Mais ce que je veux dire c’est que les choses ici vont mal

Muita careta pra engolir a transação

Des tas de grimaces pour avaler tous ces trucs

E a gente tá engolindo cada sapo no caminho

Et qu’on avale des couleuvres en chemin

E a gente vai se amando que, também, sem um carinho

Et qu’on s’aime, aussi, parce que sans la tendresse

Ninguém segura esse rojão

Personne ne supporte cette galère

Meu caro amigo eu bem queria lhe escrever

Mon cher ami j’ai bien voulu t’écrire

Mas o correio andou arisco

Mais on se fait difficile à la Poste

Se me permitem, vou tentar lhe remeter

Si on me le permet je vais te remettre

Notícias frescas nesse fita

Des nouvelles fraîches sur cette cassette

Aqui na terra ’tão jogando futebol

Ici au pays on joue au football

Tem muito samba, muito choro e rock’n’ roll

Il y a beaucoup de samba, beaucoup de choro et rock’n’roll

Uns dias chove, noutros dias bate sol

Des jours il pleut, d’autres le soleil cogne

Mas o que eu quero é lhe dizer que a coisa aqui ’tá preta

Mais ce que je veux dire c’est que les choses ici vont mal

A Marieta manda um beijo para os seus

Marieta envoie un bisou aux tiens

Um beijo na família, na Cecília e nas crianças

Un bisou à la famille, à Cécile et aux enfants

O Francis aproveita pra também mandar lembranças

Francis en profite pour également se rappeler à ton bon souvenir

A todo o pessoal

A tout le monde

Adeus

Au revoir

(Traduction de Dominique et Vagner du Forum Bossa-Nova)

Ernest Barteldes

Jemima Hunt

Michèle Voltaire Marcelin is a poet/writer, performer and painter who was born and raised in Haiti, sojourned in Chile, and currently lives in the United States. The publication of her first novel “La Désenchantée” (CIDIHCA, Montréal-2006) was followed by its Spanish translation “La Desencantada” and two other books of poetry and prose: “Lost and Found” and “Amours et Bagatelles” (CIDIHCA, Montréal-2009) - translated into Spanish by Editorial ALBA as "Amores y cosas sin importancia" - all of which garnered rave reviews. Her writings are also featured in 3 anthologies published in France: "Cahier Haiti" (published by RAL'M-2009), "Terre de Femmes" (Editions Bruno Doucey-2011) "Revue Intranqu'îllités" (2012). She speaks and writes fluently French, English, Spanish and Haitian Creole. She has a BFA from the Leonard Davis Center for the Performing Arts at CUNY and a Masters from The New School for Social Research.

Michèle Voltaire Marcelin is a poet/writer, performer and painter who was born and raised in Haiti, sojourned in Chile, and currently lives in the United States. The publication of her first novel “La Désenchantée” (CIDIHCA, Montréal-2006) was followed by its Spanish translation “La Desencantada” and two other books of poetry and prose: “Lost and Found” and “Amours et Bagatelles” (CIDIHCA, Montréal-2009) - translated into Spanish by Editorial ALBA as "Amores y cosas sin importancia" - all of which garnered rave reviews. Her writings are also featured in 3 anthologies published in France: "Cahier Haiti" (published by RAL'M-2009), "Terre de Femmes" (Editions Bruno Doucey-2011) "Revue Intranqu'îllités" (2012). She speaks and writes fluently French, English, Spanish and Haitian Creole. She has a BFA from the Leonard Davis Center for the Performing Arts at CUNY and a Masters from The New School for Social Research.

Leave a Comment